Wazema Radio:

The declaration of what was described as ‘law enforcement operation” in Tigray on November 4, 2020 was a shock to the markets. Not that it was unexpected, but it affirmed that that inevitable point of conflict between the increasingly highhanded center and the dissenting power pole in Meqelle has just arrived. For starters, the war of words, the military buildup and the economic undercurrents were going on for over two years.

Instigating the declaration was the alleged attack of Tigrian Regional forces on the relatively sophisticated and highly mechanized component of the Ethiopian National Defense Forces based in the outskirts of the Tigrian capital. In what one former official described as a “thunderous strike”, the regional forces attacked the Northern Command, seized sophisticated ammunition and sparked the fire for what seems to be a protracted conflict7

It has been 90 days and counting since Addis Ababa shut basic communications, established a regional state of emergency (SoE) and started an all-out offensive against the Tigrian Regional forces and the Tigrian People Liberation Front (TPLF). From the active participation of Eritrean forces in the conflict corroborated by various sources to the killing of high level TPLF members, such as Former Foreign Minister Seyoum Mesfin and former Minister Abay Tsehay; from aggressive propaganda campaign to reports of extrajudicial killings; and from historic diplomatic underperformance to the indifference of the international community, the conflict has opened a pandora’s box of conflicting interests of varying agencies.

Not so much talked about, however, is the economic background and impact of the conflict. Hence, this piece attempts to dive a bit deeper into the economics of the conflict.

By the time the war broke out, the Ethiopian economy was struggling to get itself organized to effectively respond to the challenges of COVID-19. Official estimates show that the pandemic drove Gross Domestic Product (GDP) down to 3.2% from estimated 10.1%, pushed closed to a million people out of jobs and led to the closure of factories. This, of course, is in addition to long standing structural challenges in the form of widening trade deficit, increasing debt distress, widespread unemployment, inflationary buildup and foreign exchange shortage.

Getting out of its long overdue statist inclination, the economy was embarking on a journey of increasing the traction of the private sector. And this was happening in the form of massive privatization push, the opening up of formerly protected sectors and instituting macro reforms, such as competitive exchange rate.

Even then, the course of action was not clear. No comprehensive policy document that articulates the rationale for reform was there – only a slide deck named the Home Grown Reform Agenda (HGRA). Officials were heard stating conflicting objectives, while cadres just parroted whatever they snick pick from the official line. The ten-year prospective plan of the government which was under drafting for the last one year is yet to be made public.

While the center was trying to bring macro balance, Tigray regional state was sitting on huge backlogs of developmental challenges. Despite the flexing of military might, which later proved to largely be deceptive propaganda, the region was home to 2.5 million people, under the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP), 600,000 households in need of emergency food assistance, 100,000 internally displaced people (IDPs) and around 200,000 Eritrean migrants. With its largely mountainous terrain deteriorated through centuries of intensive farming and deforestation, the region sees the worst rates of access to clean water supply, sanitation and access to finance.

No doubt that these vulnerabilities are huge risks anyone who foresees military confrontation would have accounted for. But TPLF did the math wrong.

Weeks before the war broke out, the Tigray Regional state issued a bond for public subscription. Although the official line was that the bond is meant to mobilize resources for development, it was obvious that it was intended to mobilize resources for what seemed to be an inevitable event. Seeing what has unfolded afterwards, however, one would say that TPLF was not strategically prepared for the conflict. It was rather too shortsighted and too reductionist in its analysis that it mistakenly took war as a military operation than a largely economic one. Such a poor misjudgment from a party that claims to know war and its running more than anyone else.

Equally, if not more, Addis Ababa was not prepared to handle and manage such a crisis. It all seems as if the war drums were not beaten even for a day, let alone for two years.

The fact that the central bank introduced new currency notes a couple of months before, with stated economic objectives of controlling money outside the bank and fighting illegal business operations, meant that Addis was making its own gamble with outcomes largely uncertain. Showcasing the later is the shifting messaging of central bank officials on what their prime objective is in changing the currency notes. At one point they were talking all about money outside the bank largely owned by TPLF sympathizers, while at another they were hyping about deposit mobilization as outstanding objective. In reality, the demonetization has largely to do with political objectives than economic ones.

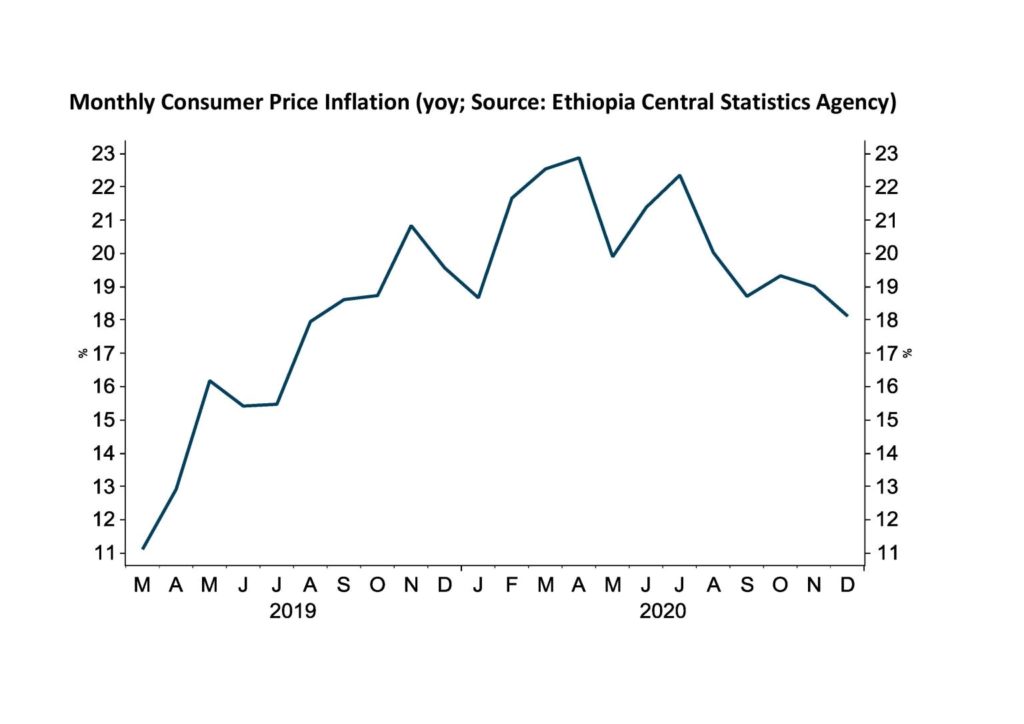

What remained puzzling is that the central bank was doing the currency change in an environment of significant political tensions and spiking headline inflation. Aggregate inflation for November was 19.3%, with food inflation upwards of 21%.

Even though they could not do anything about political risks, they should have had clear plan on how to contain inflation. Their recent baptism in the name of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) should not have barred them from seeing that Ethiopia’s inflationary pressure has much to do with supply constraints as monetary expansionism.

Beyond the monetary adjustments, Addis Ababa was also struggling to get its fiscal space in shape. Stringent project approval, barring of non-concessional loans, reforming key money-sucking state-owned enterprises (SoE) and reconsolidation of the public procurement systems were some of the measures it took in addition to the rather obvious attempt of deficit financing through floating rare year-long treasury bills.

Measures taken after November 4 show that Addis was deploying economic instruments as part of the matrix of tools of pushing TPLF to the edge. And these include freezing the accounts of TPLF conglomerates, restrictive monetary measures (such as reduction of cash withdrawal limits and regulation of individual transfers), closing of banking services in Tigray, jailing of business people with close links to TPLF and administrative measures on parallel market operators. And it is all done with the intention of closing the financial channels of TPLF.

Unfortunately, as it is with many other economic decisions, most of the measures were reflexive that they continue to haunt Addis back. In some cases, such as wholesome closure of banking services, it pushed more Tigrians to the side of TPLF.

Since the war broke out, inflation has soared in many parts of the country, with the stats in Tigray showing it to be upwards of 40%. The exchange rate of Birr against major currencies have reached an all time high of 40 Br in formal market and 54 Br in parallel markets.

Remittance and foreign direct investment have declined, forcing government agencies to run consistent face-saving campaigns. Exports faced uncertain times, although the overall figure remains stable for the time being. Foreign currency availability has worsened, impacting supply and price of imported essentials, such as medicines, children food, industrial inputs and edibles.

Property market has seen decline in valuation. And restrictive property transfer procedures instituted along with the conflict further depressed purchases.

Although there is little information on the costs of it, the war seems to be sucking in huge resources from the struggling economy. Lest, the safest gamble for Addis and its Nobel Prize Winner Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed is to resolve the situation in shorter time possible. The more time the war takes the deeper the economic black hole, taking everything down with it.

Things are already bleak in Tigray. By the accounts of the transitional administration, 4.5 million people are in need of emergency food assistance. Humanitarian blockade means the number of people dying from starvation is increasing with each day. Banking service is not yet open in most parts of the region and hence people do not have cash to buy life sustaining essentials.

Commodity supplies is halted as transportation service is not there in most parts.

Essential services, such as health care, are in doldrums with facilities looted and supplies dwindled. Civil servants are not paid for months, while robbery and vandalism have become all too common.

According to the UN, there is a total resource need of close to 69 million dollars for responding to the multifaceted crisis in Tigray. Humanitarian experts are consistently warning that each day under a humanitarian blockade means the death of more people from starvation.

Yet, Addis continues to resist opening unhindered humanitarian corridor. The guidance seems to be that all humanitarian efforts in the region ought to be organized by national agencies and be managed in the way they see fit. Nonetheless, the national humanitarian fixture seems to lack the capacity, flexibility and experience of running such massive deployment in an active conflict zone. If anything, Addis’s stance is all about sidelining the international community and acting on its own terms. It, however, seems to risk its economic credibility owed to its international suppliers, creditors, donors and trading partners.

A line from the recent assessment of the credit rating agency, Fitch, saying “we see a downside risk that the federal Ethiopian government fails to swiftly conclude its intervention in Tigray” summarizes the risk that furthering the blockage will have on the reputation of the country. It won’t be longer before this erosion of reputation crawls into real economic activities, such as as withholding of aid, as the European Union has recently decided.

In broader terms, the war is largely about ideologies. It is about an attempt by a largely liberal Addis Ababa emboldened by unquestioned support from its Western and Middle Eastern accomplices to disrupt and neutralize the strongest frontiers of state-led economic development. It is also a clash of interest groups with Addis representing an emerging network of aspiring novae riche who see their future in a rather open, outward looking, service-based and knowledge-driven economy, while Meqelle precipitating the conservative, inward looking, traditional and nationalist old guard. But at micro level, the war is a clash of economic miscalculations with Addis betting to squash its strongest rival in the shortest period of time and TPLF overlooking the essential vulnerabilities of Tigray and what it takes to win war in 21st century.

And the cost of it all is that Ethiopians, be it in Tigray as well as in other places, will be shouldering the cost of these miscalculations in both lives and livelihoods. And the longer it takes for peace to reign in, the higher the cost to paid. This certainly will make restoration of peace, rehabilitation of livelihood and reconstruction of infrastructure costlier. Such an unfortunate developmental drag and repeat of history indeed!

For the sake of the lives being lost and livelihoods being destructed, it is high time that negotiated resolution of political differences is given a genuine chance. Else, it is highly likely that we might see the worst tragedy in the country’s history unfolding in our times. Let us hope that there remain some sane minds to look for ways of negotiated solution, no matter how hard it is to achieve.

Editor’s Note: Wazema withheld the writer’s identity upon request.